I loved this graphic novel by Emil Ferris: My Favorite Thing is Monsters! It's set in 1960s Chicago and, via memory/tape, World War II. Since I lived in Chicago for 20 years as a grownup and was alive in the 1960s as a kid, I recognized a lot of places and major events, including the terrible and heartbreaking assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Chicago's devastating response to it.

The story is "told" by a young girl, Karen, who is drawing it as she goes. She's got a tough, interesting life, that's for sure, full of mystery and, yes, monsters. The girl and author see something wonderful in some monsters. "The bad monsters want the world to look the way they want it to. They need people to be afraid... Bad monsters are all about control... They want the whole world to be scared so that bad monsters can call the shots..." Yep. Good monsters are dealing with what's happened to them in ways that can include kindness, love, smarts, vulnerability, and resourcefulness.

It was great to see the Aragon Ballroom, Graceland Cemetery, and paintings from the Art Institute in this book. I think I did a poetry reading once in one of the old buildings. And my path has crossed with the fellow in the story seen as a genius by Karen's brother. The art is fantastic. It recreates the girl's notebook, down to the lines and metal spiral binding.

This is book one, and I can't wait for book two, but I'll have to; it's been delayed, as was book one. The first delays had to do with West Nile virus, a change in publishers, and a freight company going bankrupt, leaving 100,000 copies of the book stalled in a ship at the Panama Canal. I think book two is now delayed till the fall of 2021. But so is everything else!

Random reading coincidences: References to Greek myths + a character named Sonja in both The Untelling and My Favorite Thing is Monsters, along with the death of MLK, Jr. A cat in a cemetery scene in both Monsters and Empire Falls (another Richard Russo book.) It's like everything I read is fitting together. And today's random coincidence was another cool graphic novel, this one a noir story, also connected to other books, by Jules Feiffer, who I always thought of as a playwright and cartoonist. Now he's doing this, too: Cousin Joseph, a prequel to Kill My Mother (need to read), to be followed by The Ghost Script (still to come).

Friday, July 31, 2020

Thursday, July 30, 2020

Untelling

I loved Silver Sparrow and An American Marriage by Tayari Jones so much that I needed to read her other books, too, and fortunately interlibrary loan is again possible, so I got hold of The Untelling and Leaving Atlanta. The latter, set during the Atlanta child murders in 1979, is heartbreaking. Both books are continuing my anti-racist education, as I am learning about black life from black authors. In Leaving Atlanta, Tasha's father joins a search party for one of the missing children and is partnered with a white man. She overhears her father speaking privately with her mother at the dinner table. "Sometimes those decent white folks can understand that we can't forgive them." Yes. "Especially not at a time like this." We're in another terrible time now, still standing side by side, some of us, searching, and still caught in that terrible unforgiving place.

I was surprised to find "Tayari Jones" as a character in Leaving Atlanta. But it also made perfect sense, as the author was a child when the child murders were taking place. (Here's a Reader's Guide pdf about that.) I was surprised and delighted to find a character named Octavia, as I'd just been reading a lot of Octavia Butler. Coincidence?! While Octavia is the point-of-view character, she's worried about a missing boy, a friend in her class at school. Girls have giggled about a possible romantic connection there. That and the geography give us this beautiful sentence: "The sound of wind in the pecan trees was like girls giggling." Will I ever be where I can hear the wind in pecan trees?

In The Untelling, a young woman learns who she is through empathy, awareness, and suffering, and on the way to that she's not always "likable," a wonderful risk for an author to take, and she's otherwise meant to be a sympathetic character, who has survived a terrible loss. "I wanted to tell him that I knew how he felt, though I probably did not. How can you know what another person is going through when your own life is so different from his?" This is so real, so honest. "People had done this to me often enough, telling me that they knew how I felt because they had suffered this or that loss, felt some sort of pain." She's impatient with the gesture of empathy, that possibly surface connection, and decides it's probably best to say nothing: "...I could predict his response, his words, polite enough, thanking me for my empathy, my generosity of spirit. And I could imagine his thoughts, that no, I couldn't possibly empathize. Our situations were not the same at all." She's right, but is it also an excuse for not reaching out to comfort someone?

The book explores differences of class and circumstance among black characters, with differences of race in the background. But I understood that differences of race might prevent any attempt of mine to reach out in empathy to a black person, as I recognized in the words above something that had happened to me. I reached out to a black woman as a woman, and was firmly and not so politely rejected. No, being a woman was nothing like being a black woman. I got her message. But then we went through something hard together, bonded, she appreciated my support, and I feel connected to her forever. Yes, we experience life differently, for many reasons, among them the history of race relations in America, but I can accept that now, feeling the human bond with her. I can respect and honor our difference inside this deep human bond, whether she and I can ever express that to each other in words.

I was surprised to find "Tayari Jones" as a character in Leaving Atlanta. But it also made perfect sense, as the author was a child when the child murders were taking place. (Here's a Reader's Guide pdf about that.) I was surprised and delighted to find a character named Octavia, as I'd just been reading a lot of Octavia Butler. Coincidence?! While Octavia is the point-of-view character, she's worried about a missing boy, a friend in her class at school. Girls have giggled about a possible romantic connection there. That and the geography give us this beautiful sentence: "The sound of wind in the pecan trees was like girls giggling." Will I ever be where I can hear the wind in pecan trees?

In The Untelling, a young woman learns who she is through empathy, awareness, and suffering, and on the way to that she's not always "likable," a wonderful risk for an author to take, and she's otherwise meant to be a sympathetic character, who has survived a terrible loss. "I wanted to tell him that I knew how he felt, though I probably did not. How can you know what another person is going through when your own life is so different from his?" This is so real, so honest. "People had done this to me often enough, telling me that they knew how I felt because they had suffered this or that loss, felt some sort of pain." She's impatient with the gesture of empathy, that possibly surface connection, and decides it's probably best to say nothing: "...I could predict his response, his words, polite enough, thanking me for my empathy, my generosity of spirit. And I could imagine his thoughts, that no, I couldn't possibly empathize. Our situations were not the same at all." She's right, but is it also an excuse for not reaching out to comfort someone?

The book explores differences of class and circumstance among black characters, with differences of race in the background. But I understood that differences of race might prevent any attempt of mine to reach out in empathy to a black person, as I recognized in the words above something that had happened to me. I reached out to a black woman as a woman, and was firmly and not so politely rejected. No, being a woman was nothing like being a black woman. I got her message. But then we went through something hard together, bonded, she appreciated my support, and I feel connected to her forever. Yes, we experience life differently, for many reasons, among them the history of race relations in America, but I can accept that now, feeling the human bond with her. I can respect and honor our difference inside this deep human bond, whether she and I can ever express that to each other in words.

Tuesday, July 21, 2020

Best We Could Do

After Chances Are... by Richard Russo, on Martha's Vineyard, I did not make it to Cape Cod for That Old Cape Magic, which was not at hand in the stacks at the library, so I opted for Bridge of Sighs, instead, set in the small town of Thomaston, New York, and sometimes Venice, Italy, with some graphic novels in between, and right after. Indeed, a certain phrase in Bridge of Sighs, about families doing "the best we can do," was the bridge to The Best We Could Do, an illustrated memoir by Thi Bui.

Thi Bui tells and draws the story of her family coming to America from Vietnam, after the war, via boat and refugee camp, as well as the story of coming to understand her parents better after becoming a parent herself. It's lovely and honest, and made me think. I realize it's part of my ongoing education this summer in equity, diversity, inclusion, and anti-racism.

As always I was aware of the random coincidences. In Bridge of Sighs, the town is poisoned by chemicals and dyes from the local tannery, that get poured into Cayoga Stream. In The Best We Could Do, the author's father helps create a small town, building roads and houses, creating a pleasant, self-sufficient environment with a well-stocked pond, until a fabric dyer moves to town, pours her dyes into the pond, and kills all life in it.

Both books tell a family saga and explore the love and a reticence born of trauma that can affect relationships for a long time. Both move toward even deeper love and understanding, and leave some things unsaid, uncertain. Both made me think about, miss, and connect with my own family.

Thi Bui tells and draws the story of her family coming to America from Vietnam, after the war, via boat and refugee camp, as well as the story of coming to understand her parents better after becoming a parent herself. It's lovely and honest, and made me think. I realize it's part of my ongoing education this summer in equity, diversity, inclusion, and anti-racism.

As always I was aware of the random coincidences. In Bridge of Sighs, the town is poisoned by chemicals and dyes from the local tannery, that get poured into Cayoga Stream. In The Best We Could Do, the author's father helps create a small town, building roads and houses, creating a pleasant, self-sufficient environment with a well-stocked pond, until a fabric dyer moves to town, pours her dyes into the pond, and kills all life in it.

Both books tell a family saga and explore the love and a reticence born of trauma that can affect relationships for a long time. Both move toward even deeper love and understanding, and leave some things unsaid, uncertain. Both made me think about, miss, and connect with my own family.

Thursday, July 16, 2020

Fever Year

Graphic novels are a great way to receive a lot of information. That is certainly the case with Fever Year: The Killer Flu of 1918, by Don Brown. This was intentional "covid reading," so I could gauge age appropriateness of this book for a possible future Browser Pack at the library. One family had requested books on Covid-19 for kids (I don't think there are any yet), but I knew we had this. It's more appropriate for a teen than a youngster, given the amount and darkness of the facts.

This book, published in 2019, right before the current pandemic, is dedicated "to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, an underappreciated American treasure."

Here are the "fun facts" and, of course, not-so-fun facts about the flu pandemic of 1918, which killed more people than combat did in the Great War, known eventually as World War I:

Word origin: flu/influenza. Italians thought it came from "celestial influence" and called it ex influential colesti, which got reduced to una influenza in common speech.

"Spanish flu": The 1918 flu pandemic appears to have begun in the United States and got to Europe via "doughboys" during the war. There it proliferated and returned, affecting soldiers, the Red Cross nurses who tended them, and many civilians. When it got to Spain, it got the nickname "the Spanish flu" because Spain felt free to report on the illness without revealing weaknesses related to military preparedness. Spain did not like being blamed for the pandemic. (We know of the similar misnomer attached to the current virus.) Also inaccurately, people blamed the flu, and everything else, on the Germans.

Famous survivors of the 1918 pandemic: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Walt Disney (who got it at 16 and then went to France as an ambulance driver), President Woodrow Wilson (at a peace conference in 1919), Mahatma Gandhi, Katharine Anne Porter, who wrote Pale Horse, Pale Rider about the flu, which killed her fiance and split her life in two.

Animals: No one knows for sure where it started, but it might have been "a wild aquatic bird," whose droppings infected chickens and ducks, then people, or pigs, and then people. In the search for a vaccine, a ferret sneezed on a human and gave him the flu.

Wax: The flu virus can survive in a sliver of lung sealed in a block of paraffin. Alas!

Waves: The 1918 flu pandemic was not over in 1918. It had resurgences until 1922.

Numbers: About a third of the world's population got infected. At least 50 million people died, probably more. The figures are estimates, and, then as now, uncertainty rules.

Masks: People fought over masks in the past, as they do now. Schools and theatres were closed. Masks kept the disease in check in some areas, and in some places masks were the law, and people were arrested for not wearing them. Imperfect use of and knowledge about masks, though, meant infection and death rate remained high.

False cures: camphor & garlic necklaces, goose grease, salt up the nose, nightcaps (the kind you wear on your head), onions, alcohol and rest and mustard plasters, coal smoke mixed with sulfur or brown sugar, home brewed smelly "medicine." (We may recall similar false cures recently in the news.) So there you have it, including Ebenezer Scrooge in a nightcap (in an illustration by John Leech).

This book, published in 2019, right before the current pandemic, is dedicated "to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, an underappreciated American treasure."

Here are the "fun facts" and, of course, not-so-fun facts about the flu pandemic of 1918, which killed more people than combat did in the Great War, known eventually as World War I:

Word origin: flu/influenza. Italians thought it came from "celestial influence" and called it ex influential colesti, which got reduced to una influenza in common speech.

"Spanish flu": The 1918 flu pandemic appears to have begun in the United States and got to Europe via "doughboys" during the war. There it proliferated and returned, affecting soldiers, the Red Cross nurses who tended them, and many civilians. When it got to Spain, it got the nickname "the Spanish flu" because Spain felt free to report on the illness without revealing weaknesses related to military preparedness. Spain did not like being blamed for the pandemic. (We know of the similar misnomer attached to the current virus.) Also inaccurately, people blamed the flu, and everything else, on the Germans.

Famous survivors of the 1918 pandemic: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Walt Disney (who got it at 16 and then went to France as an ambulance driver), President Woodrow Wilson (at a peace conference in 1919), Mahatma Gandhi, Katharine Anne Porter, who wrote Pale Horse, Pale Rider about the flu, which killed her fiance and split her life in two.

Animals: No one knows for sure where it started, but it might have been "a wild aquatic bird," whose droppings infected chickens and ducks, then people, or pigs, and then people. In the search for a vaccine, a ferret sneezed on a human and gave him the flu.

Wax: The flu virus can survive in a sliver of lung sealed in a block of paraffin. Alas!

Waves: The 1918 flu pandemic was not over in 1918. It had resurgences until 1922.

Numbers: About a third of the world's population got infected. At least 50 million people died, probably more. The figures are estimates, and, then as now, uncertainty rules.

Masks: People fought over masks in the past, as they do now. Schools and theatres were closed. Masks kept the disease in check in some areas, and in some places masks were the law, and people were arrested for not wearing them. Imperfect use of and knowledge about masks, though, meant infection and death rate remained high.

False cures: camphor & garlic necklaces, goose grease, salt up the nose, nightcaps (the kind you wear on your head), onions, alcohol and rest and mustard plasters, coal smoke mixed with sulfur or brown sugar, home brewed smelly "medicine." (We may recall similar false cures recently in the news.) So there you have it, including Ebenezer Scrooge in a nightcap (in an illustration by John Leech).

Wednesday, July 15, 2020

Back to Butler: Kindred

After my excursion to

Martha’s Vineyard via Richard Russo, I went back to Octavia E. Butler, this

time via Kindred, the graphic novel

adaptation by Damian Duffy (words) and John Jennings (illustrations). Kindred is perhaps Butler’s most well

known work, and it involves time travel from 1976 back to the antebellum era in

the American South. The time travel aspect may keep it in the science fiction

genre, but it doesn’t rely on science nor provide any scientific mechanism or

explanation for the time travel, and Butler considered it a “grim fantasy”

instead. It is indeed grim and horrific in terms of its violence—physical and

psychic—since a modern black woman travels back to a time of slavery, suffers

in her new home/present, and has to keep figuring out why, and returning or

staying in order to accomplish a particular important thing. You’ll want to

read either the graphic novel or the novel itself to find out!

For me, Kindred is part of my education this

summer in racism and anti-racism. Butler as author and Dana as main character,

who is a writer like Butler, doing work she doesn’t like to support work she

does like, has to confront her connection to white people through marriage and

lineage. In this way the present is wrapped up in the past, depends on the

past, can’t be extricated from the past—and there you have it: systemic racism

(now) and the complexity of the human, social, and economic circumstances (then)

that led to the Civil War and, alas, continue unresolved today and are emerging

in hateful, newly violent ways.

Here’s an interview with

the adaptors and here’s a wonderful reader response/comparison of

novel to graphic novel by Rachel Rae’ on YouTube. Rachel takes issue with Dana’s haircut and how it’s hard to tell if she’s a man

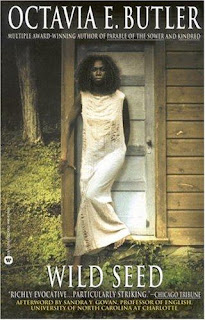

or a woman. Since I had just read Wild

Seed, with a shape and gender shifting central character, I was ready for

the visual confusion and found it fit our current times, more fluid in gender

identifications, definitions, and associations.

Duffy and Jennings note that

Dana’s haircut resembles Butler’s haircut, a way of visual representing the

autobiographical similarities there. They also added some in-jokes, I think! One Dana's jobs is at Doro's Cantina, another at Clay's Chips. Doro and Clay are characters in the linked novels of Seed to Harvest. Interesting that Kindred, the graphic novel, came

out in 2017 and has gotten even more pertinent than ever. I hope it sends

readers back to Kindred, the

original, by Octavia E. Butler.

And it definitely prepares me for Antebellum, a horror film starring Janelle Monae, due out in August

but Covid-postponed (?), with some basic plot similarities to Kindred. IMDB asks but doesn’t yet

answer the question of whether the film is partly based on the novel. The main character

is an author, like Dana, but her name is Veronica. The trailer shows me that

the little boy from the past is now a little girl. Veronica’s husband is black,

not white. But, indeed, sudden time travel places a black woman of now into a

plantation of the past. Hmm.

Thursday, July 9, 2020

Old Lady Sweaters

Up until recently, I had two old lady sweaters, both aqua, the color of pools in Florida, after the old ladies have moved there. Indeed, both had belonged to old ladies in Florida, ladies I loved. One belonged to my Grandma Sid, and I kept it as a souvenir of her life. It had big buttons (just a few), clean lines, and a large fold-down collar. I wore it till I wore it out, and then I said goodbye. The other one belonged to my mother-in-law, and I took this one to work to wear in the air conditioning. It's still there--I wore it today!--but the top button popped off, a yarn-covered button, and it sits in the bottom of my tote bag that reads, "I Like Big Books and I Cannot Lie" until that possible Someday when I sew it back on. But first, I need to mend a ribbon (again) on one of my fabric masks.

I like big books, and I cannot lie. So I have to confess that this image is not my actual book bag, but a similar one. (And the colors remind me of Dunkin' Donuts.) I couldn't find an image of my actual book bag, which came from a library convention exhibits hall. And I have to tell you that as soon as I dedicated my summer to black authors, I realized I had been neglecting Richard Russo, an old white man. I've loved him since Straight Man (hilarious) and Nobody's Fool, and he's written lots of books since then that I failed to read. So now I am reading Chances Are... which is about old white men, but also when they were young. "Three goddamn old men," as it says on page 30.

It's also "an astute portrait of a thirty-year marriage, in all its promise and pain," according to a blurb on the book jacket. That, and my recent neglect of old white men in general, made me pick it up, soon after reading An American Marriage, a wonderful book by Tayari Jones. Everybody said it was wonderful, it was checked out all the time when it was new to the library, and we had two copies available, right after I finished Silver Sparrow, another wonderful book, about sisters, by Tayari Jones, so I snatched up and loved it all the way through.

So I am still reading black authors this summer, but, for a moment, this old white lady is reading an old white man. In the back yard on another hot day. As soon as I step away from this computer, in this cool lower-level home office, not wearing an old lady sweater.

UPDATE (weather and otherwise), next morning: truly cool now after a truly loud thunderstorm last night! Chances Are... is definitely not about "a thirty-year marriage, in all its promise and pain." Turns out that blurb is about That Old Cape Magic, info obscured by the necessary library item-number label! So, after Martha's Vineyard, I might have to head to Cape Cod.

I like big books, and I cannot lie. So I have to confess that this image is not my actual book bag, but a similar one. (And the colors remind me of Dunkin' Donuts.) I couldn't find an image of my actual book bag, which came from a library convention exhibits hall. And I have to tell you that as soon as I dedicated my summer to black authors, I realized I had been neglecting Richard Russo, an old white man. I've loved him since Straight Man (hilarious) and Nobody's Fool, and he's written lots of books since then that I failed to read. So now I am reading Chances Are... which is about old white men, but also when they were young. "Three goddamn old men," as it says on page 30.

It's also "an astute portrait of a thirty-year marriage, in all its promise and pain," according to a blurb on the book jacket. That, and my recent neglect of old white men in general, made me pick it up, soon after reading An American Marriage, a wonderful book by Tayari Jones. Everybody said it was wonderful, it was checked out all the time when it was new to the library, and we had two copies available, right after I finished Silver Sparrow, another wonderful book, about sisters, by Tayari Jones, so I snatched up and loved it all the way through.

So I am still reading black authors this summer, but, for a moment, this old white lady is reading an old white man. In the back yard on another hot day. As soon as I step away from this computer, in this cool lower-level home office, not wearing an old lady sweater.

UPDATE (weather and otherwise), next morning: truly cool now after a truly loud thunderstorm last night! Chances Are... is definitely not about "a thirty-year marriage, in all its promise and pain." Turns out that blurb is about That Old Cape Magic, info obscured by the necessary library item-number label! So, after Martha's Vineyard, I might have to head to Cape Cod.

Wednesday, July 8, 2020

Seed to Harvest

It may be a dry July, but it's got drama. Some trees and branches came down around town in a brief rainstorm today, followed by more heat, but things got watered. I love growing plants from seed, especially perennials that will drop more seed and come back next year or the year after that, according to conditions. And I collect seeds, too, to scatter where they might like to grow.

For me, this will be a summer of reading black authors writing what they like to write. I've recently been wrapped up in Seed to Harvest, a collection of four novels by Octavia E. Butler. Wow, what a saga! It's like all of human history, and a bit extraterrestrial history on Earth, imagined side by side with how I previously "knew" it, a kind of speculative fiction before we called it that. Octavia E. Butler was known as a science fiction writer, and Wikipedia tells me she was the first scifi writer to win a MacArthur Fellowship!

In the novels collected here, Butler's imagined history and future of humanity shows it in all its brutality, as a constant, violent struggle for dominance, sometimes eased by compassion, telepathy, and amazing healing powers. Wild Seed is the origin story, where we meet Doro, basically immortal, as long as he can feed on people and breed them for the world he wants to control. He contends with the shapeshifter Anwanyu, a woman (and sometimes a man) who can heal, who feels deeply for people, and who finds freedom and relief from human conflict by being a dolphin or a bird.

The animal morphing reminded me of Merlin teaching the young King Arthur! I loved the special powers of the people in Butler's linked stories. It reminded me of a series of stories by Zenna Henderson about The People, who had special powers they had to hide in order to fit in, and it turns out Octavia Butler like Zenna Henderson, too!

The other novels here are Mind of My Mind, Clay's Ark, and Patternmaster, the culmination of the series, but actually written first. It's not just movies that have prequels! And wouldn't you know it, along with the brutal quest for power, there was highly contagious disease. Clay's Ark brings in a virus-like illness from outer space. "And the disease organism could live on the skin for hours in spite of normal, haphazard handwashing." Back in 1984, when this came out, we weren't all watching videos on how to wash our hands, or singing songs while doing it.

"Listen! We're infectious for as much as two weeks before we start to show symptoms... How many people do you think the average person could infect in two weeks of city life? How many could his victims infect? ...There is no cure, ...and by the time one is found--if one can be found--it will probably be too late."

So that was pretty pertinent. Butler gripped me, that's for sure. And I was so ready for and grateful for this beautiful sentence when it came: "They held each other until they could no longer tell which of them was trembling." I admired her wisdom and patience as a writer, her willingness to leave uncertain and unfinished what can't be known or resolved, and her ability to write a satisfying ending nonetheless.

For me, this will be a summer of reading black authors writing what they like to write. I've recently been wrapped up in Seed to Harvest, a collection of four novels by Octavia E. Butler. Wow, what a saga! It's like all of human history, and a bit extraterrestrial history on Earth, imagined side by side with how I previously "knew" it, a kind of speculative fiction before we called it that. Octavia E. Butler was known as a science fiction writer, and Wikipedia tells me she was the first scifi writer to win a MacArthur Fellowship!

In the novels collected here, Butler's imagined history and future of humanity shows it in all its brutality, as a constant, violent struggle for dominance, sometimes eased by compassion, telepathy, and amazing healing powers. Wild Seed is the origin story, where we meet Doro, basically immortal, as long as he can feed on people and breed them for the world he wants to control. He contends with the shapeshifter Anwanyu, a woman (and sometimes a man) who can heal, who feels deeply for people, and who finds freedom and relief from human conflict by being a dolphin or a bird.

The animal morphing reminded me of Merlin teaching the young King Arthur! I loved the special powers of the people in Butler's linked stories. It reminded me of a series of stories by Zenna Henderson about The People, who had special powers they had to hide in order to fit in, and it turns out Octavia Butler like Zenna Henderson, too!

The other novels here are Mind of My Mind, Clay's Ark, and Patternmaster, the culmination of the series, but actually written first. It's not just movies that have prequels! And wouldn't you know it, along with the brutal quest for power, there was highly contagious disease. Clay's Ark brings in a virus-like illness from outer space. "And the disease organism could live on the skin for hours in spite of normal, haphazard handwashing." Back in 1984, when this came out, we weren't all watching videos on how to wash our hands, or singing songs while doing it.

"Listen! We're infectious for as much as two weeks before we start to show symptoms... How many people do you think the average person could infect in two weeks of city life? How many could his victims infect? ...There is no cure, ...and by the time one is found--if one can be found--it will probably be too late."

So that was pretty pertinent. Butler gripped me, that's for sure. And I was so ready for and grateful for this beautiful sentence when it came: "They held each other until they could no longer tell which of them was trembling." I admired her wisdom and patience as a writer, her willingness to leave uncertain and unfinished what can't be known or resolved, and her ability to write a satisfying ending nonetheless.

Tuesday, July 7, 2020

My Dry July

Just the other day, my husband found in the garage a bucket full of colored sidewalk chalk that I'd been looking for in the basement. So there's that for the next public art project that might arise from the ongoing circumstances. And I ordered and received a little box of slim white chalkboard chalk for the next round of daily poems, possibly in September. For now, I'm writing in my various journals, intermittently.

As I've been writing here, I've been hearing thunder! And, look, it's raining out my window! ...And now I've come back from stepping outside to smell the rain, the needed rain, the gentle rain. It's falling on my prairie flowers, my single tomato plant, my little pots of hibiscus tea, my gradual attempts at a very local permaculture. I forgot to plant a little packet of California poppy seeds, but I have plans for it. I have more to tell you, but not right now.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)